Its physical fabric has undergone many changes, including the addition of a contemporary arts wing that opened in 2008, overlooking our popular garden. While its original purpose has changed, the building has been in more or less continuous use for three centuries, a witness to Liverpool’s fluctuating fortunes, and it remains an iconic presence at the heart of the city’s culture.

The Bluecoat’s architectural importance is reflected in its Grade I listing. The building is also significant as a symbol of the birth of ‘modern Liverpool’, the early years of the eighteenth century when the port started to capitalise on its Atlantic-facing position and a revolutionary new dock infrastructure. This gave it a competitive edge over rivals Bristol and London, and maritime trade, particularly with the colonies, brought great wealth to the port, while contributing to the expansion of Britain’s empire.

Many Liverpool merchants involved in this process supported the Blue Coat Hospital (as the charity school was known), both in its construction and maintenance.

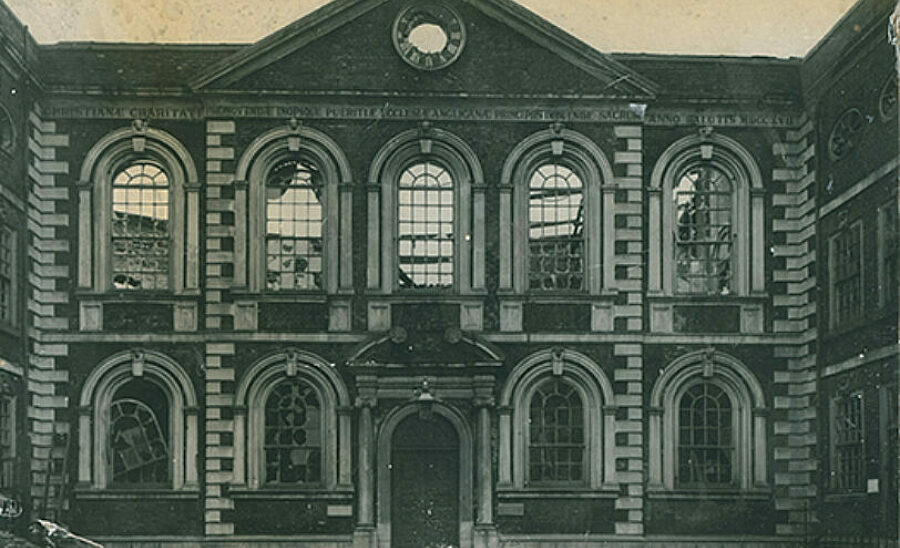

As indicated in the Latin inscription that is still above the main entrance, the school was ‘dedicated to the promotion of Christian charity and the training of poor boys in the principles of the Anglican church. Founded in the year of salvation 1717’.

The original school was founded in 1708 by the rector of Liverpool, Reverend Robert Styth, and master mariner Bryan Blundell, a modest building opposite St Peter’s Church. The present building superseded this, a much larger boarding school where children learnt to ‘read, write and cast accounts’. A brick kiln was set up on the site in 1715, a foundation stone laid in 1716, and two years later the first 50 boarders - boys and girls - moved in, two thirds of their time being taken up in tasks to generate income for the school, a third in lessons. In 1722, alms houses were erected to the rear of the building and construction was completed in 1725 at a cost of just under £2,300.

Bryan Blundell (c.1675–1756), the school’s principal benefactor and treasurer, supported the school throughout his life, as did his sons, encouraging other merchants to subscribe, donate or leave legacies, or become trustees.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Liverpool was the most prominent British transatlantic slave port and the Blundell family, and many of their merchant colleagues were involved, either as slave-ship captains or owners, or in industries like sugar, tobacco and cotton that the trade in enslaved Africans enabled. Academic research supported by the arts centre reveals the extent of these merchants’ slavery-related businesses: Sophie Jones’ Subscriptions, Schooling, Slavery: Bluecoat’s Early Years and Michelle Girvan’s current research into Bryan Blundell.

Since the 1980s, several artists have interrogated the building’s school history and its connections to mercantile trade, including slavery, and there is information on these in our library collection, The Bluecoat and Slavery.

The architect of the Bluecoat building has caused much speculation. Recent research has confirmed that Liverpool’s dock engineer Thomas Steers, together with mason Edward Litherland, are the most likely contenders (see Chapter 1 Bluecoat, Liverpool: The UK’s first arts centre). Both received considerable payments, recorded in the school’s meticulous accounts book. They also worked together on other schemes in Liverpool, notably the nearby Old Dock, completed just before the Blue Coat in 1715.

This connection to the world’s first commercial wet dock is significant, with many pupils being apprenticed to local employers involved in shipping, some becoming mates or masters of ships, many emigrating to the colonies. Others followed very different careers: Richard Ansdell became a Royal Academician and successful painter; his The Hunted Slaves (1861) now hangs in Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum.

A fine example of Queen Anne architecture (though actually built during George I’s reign), Bluecoat’s distinctive features include Liverpool’s earliest liver birds, over the gate and doorways in the cobbled front courtyard. Also of note are a one-handed clock, cherubs’ heads over the windows, and oval windows above these. Graffiti from the eighteenth century, carved into cornerstones in a secluded part of the courtyard, was probably made by pupils of the school. The cupola on the roof once supported a weathervane of a ship, symbolising the importance of maritime trade to the institution. This features in a 1718 engraving (see image above), produced to raise money for the school, which includes other architectural details that have since disappeared: statues on the pediment denoting faith, hope and charity; balustrades and flambeaux; and checkerboard paving covering the courtyard, though it is doubtful this was ever realised. Apart from these differences, the building’s front façade is little changed.

During the nineteenth century the school continued to grow, extending up School Lane, and there were many alterations to the building, including an enlargement of the central block with a curved extension into the rear yard, the present garden. This allowed for a spacious refectory downstairs and the installation of a Willis organ in the chapel upstairs. The courtyard was later enclosed with the addition of a single-story building on College Lane, through which there is today an arched entrance into the garden.

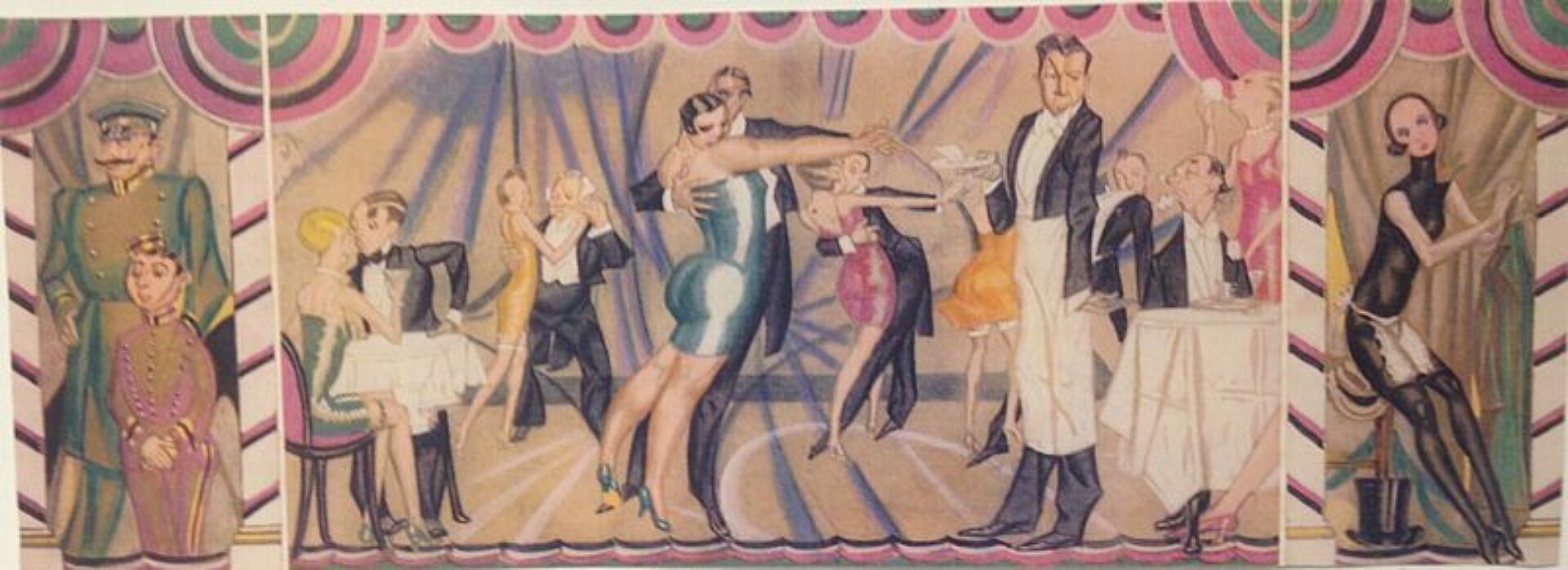

In 1906 the school finally outgrew its premises and moved to a new building in Church Road, Wavertree, where it remains today. A new chapter began the following year when a group of young artists, Sandon Studios Society moved into the vacant school building and established an arts presence that continues today. The Sandon was instrumental in securing the building’s future and the establishment of the UK’s first arts centre in 1927 under the custodianship of Bluecoat Society of Arts. Under this new ownership, the building’s interior was largely remodelled with dedicated spaces for performances, exhibitions and offices, alongside the existing artists’ studios and dining room whose visitors included Stravinsky, George Bernard Shaw and dancers from the Ballets Russes.

Tragedy struck in May 1941 when the Bluecoat suffered considerable damage from aerial bombing during the Liverpool blitz. The South wing bore the brunt of this, especially the section overlooking the garden, and this had to be demolished. The grand concert hall upstairs, directly above the current ground floor reception and café, was also destroyed.

After the war, the building was restored and the arts centre came back to life during the 1950s, although it had managed to maintain an arts programme, hosting many exhibitions organised by the Walker Art Gallery while it was closed during and immediately after the war. Other than minor interior alterations and the addition of ramps to the main entrance and in the garden, the next 50 years saw few changes, despite the presence in the building of several architectural practices and the growing national reputation of Bluecoat’s arts programme, which could have warranted capital investment in its spaces.

By the end of the millennium however, plans had been drawn up for a major scheme to build a new arts wing to replace the one damaged in the war. Together with a complete restoration of Bluecoat’s historic fabric, internal access improvements, and a re-landscaped garden, this was completed in 2008, the building reopening in time for Liverpool’s year as European Capital Culture, in which the Bluecoat played a prominent role. The architects of the scheme were Rotterdam-based practice, Biq Architecten working with project architects Austin-Smith: Lord. In 2021 the ground floor lobby area, known as the ‘Hub’, was remodeled by Liverpool-based Architectural Emporium, which improved the visitor experience.

Many of the architectural changes outlined here are charted in our Conservation Plan and there is more material available in our architecture collection. A short guide to our history is also available in this booklet, and in the Library section of the Bluecoat website.

And you can read more about Liverpool's oldest building and its development as an arts centre in a new book, Bluecoat, Liverpool: The UK's First Arts Centre.

The building underwent a second capital development project in 2021.

This time the refurbishment was to its Hub and Café area, a development that re-configured the downstairs space, and placed art at the centre of the public areas. New commissions by Babak Ganjei and Sumuyya Khader added vibrant focal points to the Hub. Harold Offeh created a bespoke family zone, designing a welcoming and creative space.

Full of busy boards, books, and activity packs, it provides somewhere for families to play and relax during their visit. The redevelopment made both the café and ticketing desk more accessible and aimed to improve the overall visitor experience at the Bluecoat. The redevelopment also aimed to make the building more sustainable. Watch our film with Mersey Forest to find out more:

This commitment to opening up access to art and ensuring its future for the public is central to the Bluecoat. The organisation continues to develop a programme that breaks new ground and now stretches far beyond its building’s walls, but the Bluecoat’s galleries, studios and public spaces will always provide a home in the city centre for art, artists and visitors alike.