You are returning to the city with Twentieth-Century Chapel. Can you outline your plans and say why it was important to locate the work here?

The project is a continuation of an installation made ten years ago at St. Luke’s Bombed Out Church. I got the feeling that the church and the Bluecoat had a rather unique role in Liverpool life – both very down to earth and accessible - and I wondered about ways of celebrating this.

Having always worked with themes of twentieth-century history, I had the idea of 'completing' the chapel begun at St. Luke’s in 2010 by decorating it with frescos based on scenarios from 1900 to the present day, creating a real life 'relic' with the appearance of something that might have been part of the original, now semi-derelict, church.

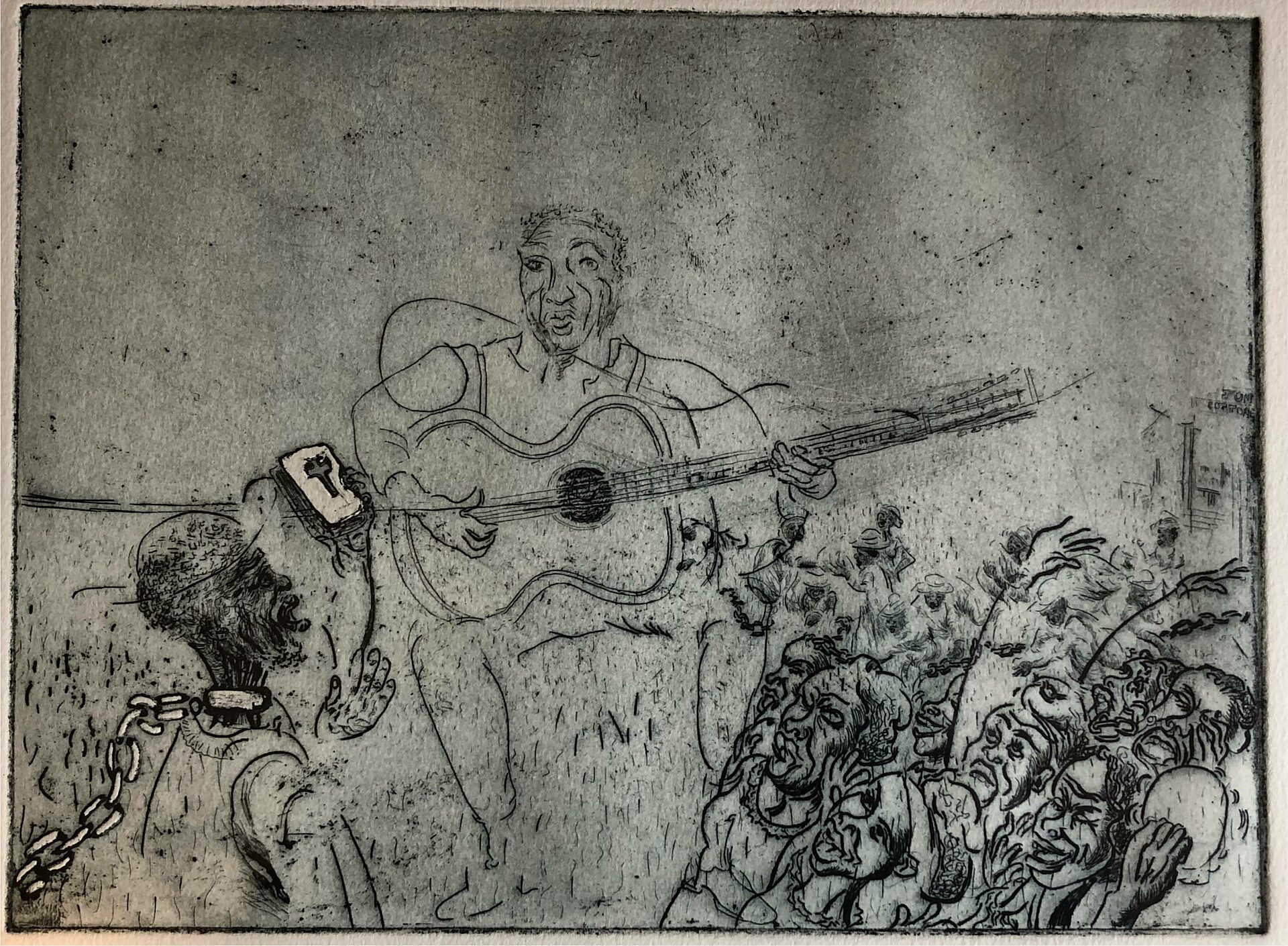

A summary of the same historical period is being created in the form of 12 etchings to be shown as 12 Decades at Bluecoat. My idea is to unite the two venues by a publicly visible art trail of painted 'plaques' mounted on buildings, from Bluecoat to the Bombed Out Church, via Bold Street – and back through the Ropewalks district. The trail leads the viewer from a traditional gallery setting, through the streets, to the ruined church, becoming the real-life testimony of the story told in the artworks - from art to reality.

As a multi-venue, open-air art event, it seemed a good idea to propose it for the Liverpool Biennial Independents 2020. With the help of Bluecoat and the Bombed Out Church I received Arts Council funding for research and development, which enabled me to build the first stage of the chapel and study the technique of fresco painting. The exhibition, chapel, and art trail are currently being prepared for a joint launch during the re-scheduled Biennial (March to June), with the hope that the art trail may remain a semi-permanent feature, uniting these two significant city centre buildings.

You have always interrogated history in your work through ambitious projects like The History of the Twentieth Century. Why does history continue to fascinate you, and what role does research play in your art-making process?

I’ve always felt that a real understanding of who we are and why we behave the way we do cannot be approached without some idea of the processes that have shaped contemporary life. I conform to the Marxist materialist concept of history, in which the basic economic struggle for existence is at the heart of all the social structures and values that dominate human life.

The wonderful scientific inventions that drove the optimism of the dawn of the twentieth century, combined with revolutions in the world of art, painted a hopeful picture for mankind in the coming modern age. Two world wars, nuclear bombs, and increasing inequality testify to the woeful contradiction between the potential of technological advancement and the material conditions of the majority of people on the planet.

As an artist I am concerned primarily with vision. A portrait of contemporary life only limited to what is seen at any one place and time may well reveal something significant but, for me, the true context lies elsewhere, in other places and earlier times. This approach, and the richness of facts unearthed from research, allows art to carry out what, for me, is its most important role – to reveal something that would otherwise remain invisible.

You first exhibited at Bluecoat in Black Art: Plotting the Course (1989), then with the Jazz prints in 1993, followed by a large solo show, The City in 1994. That exhibition focused on three cities you know – Liverpool, Paris, New York - each with a particular relationship to the growth of capitalism or modernity. The work is both celebratory and sceptical of the idea of progress and technological advance. Is that evident in the new work?

The Twentieth-Century Chapel is an amalgam of many motifs I discovered working on Guide to the Twentieth Century (completed 1999). Whereas the former was a chronological survey, the current work attempts to present recent history as the glorified episodes of a remote civilisation. This allows us to 'look back' at ourselves with the detachment of an outside observer, as if witnessing a separate species almost. The sacred format poses the irony of our unflinching embracing of the phenomena of our own age – whether this be the myriad electrical commodities that have revolutionised life, or the brand logos and celebrity imagery of our digitised screen reality.

Each of the 'sacred' plaques in the art trail extols the achievement of a successive model of aircraft - the holy embodiment of progress. This is the case, whether celebrating the first powered flight of 1903, the moon-landing, or the release of nuclear bombs and the remote warfare of our current ‘age of drones’.

Printmaking is a key part or your practice, alongside drawing, painting and installation. Can you describe how the etching process seems to suit your way of working so well?

I have certainly inherited the British tradition of graphic narrative. Social comment through illustrated episodes – exemplified by the prints of William Hogarth – is as fresh and effective as journalistic exposé. Stories showing day-to-day human scenarios at play in society evoke human experience as theatre.

Printmaking derived from the mass dissemination of news – updating the latest twists and turns in the farce that is the human drama. Printmaking is generally devoid of the contemplative depth and layering of colours and texture found in the practice of painting. The marvelous shorthand of line and black-and-white tone is ideal for capturing the essence of life in all its ephemeral vitality. It is, perhaps, like the difference in literature between a poem and a novel.

The unfortunate antics of the protagonist in Hogarth's Rake's Progress, or the characters of Francisco Goya's Caprichos, are sorry victims of the human comedy, a masquerade of vanity, dashed hopes and cruelty. Likewise, my figures – such as the child in a gas mask in the etching ‘1930s’ from the current series 12 Decades - are subject to the whims of their social predicament.

The above-mentioned series exploit the properties of the etching process, in which a metal plate can be re-worked after the first state is printed, adding new marks on top of the old, to produce a sequence of prints that reveal a step-by-step mutation of the original image. This is an ideal way to reflect the changing imagery of time – with recent episodes being overlaid on previous ones, which become the 'ghosts' or 'scars' of the past, as they fade beneath the bolder imagery of the present.

Your History of the Benin Bronzes print series from 1984 has struck a chord once again today, with fresh calls to return the bronzes to Nigeria as part of moves to challenge the story of Britain’s imperial and colonial past. What do you think the role of art is in this process of decolonisation?

Artists have the right to be as political in their work as they wish. Propaganda and art have always been intertwined, often without the conscious knowledge of the artists themselves. I am wary of characterising my own work as ‘political’ – not because it doesn't provoke political argument (I hope it does), but because it is not a political act in itself; and I value those people who engage in actually fighting for our rights too much to wish to suggest that my own work as an artist has as much political significance.

My work on the Benin bronzes was not only a testimony to colonial appropriation but also to the immutability of the art object in the face of changed cultural contexts, and the inevitable consequences of art being re-interpreted when it leaves the hand of the creator and enters the art market.

I don't really have a view on 'decolonisation', but in my work with museums I am aware of their increased concern with redefining their role as educators, and collaborating with indigenous peoples to reach agreements on the treatment of objects in collections, and their eventual repatriation. If art can help this process, all the better, and I suggest it needs to be tailormade for specific cases. A process of 'letting go' applied to acquisitions of contested ownership might be a healthy direction for museums to take, if negative remnants of the colonial past are to be erased.

You were born and grew up in Liverpool - what sent you on your journey to art school and what was studying in the North West like then?

I have always been interested in creative arts. Growing up in Liverpool during the 1950s and 60s, music was of course a primary influence. But poetry, art, theatre and dance were also very present. It was a good time to be working class and young: the benefits of post-war education and welfare, an emerging youth culture, and the championing of working-class life as subject matter for art – particularly in film, theatre, and literature – gave confidence to a generation of artists in all fields.

The hippy revolution had laid the ground rules for 'doing your own thing' by the time I started a foundation art course at Lancaster Art College in 1969. Originally believing I was studying for a 'career in art', I chose relief-sculpture design but soon realised that visual art was a tool for saying something about the world in which we live, and my future was based on the need to pursue that conviction. Post-college (1973), I was drawn back to the town by this artistic environment and became involved in a multi-media street-theatre group, Earthbound, which brought together strands of creative young people. This gave me a grounding in what was to become 'community arts'.

The 'do your own thing' philosophy was a formative experience for many young people in the 1970s, who found opportunities to express themselves through exhibitions and performance, often linked to community engagement. By comparison, today's options for young artists seem fewer, limited to 'open submission' shows. In those days, municipal galleries in the North West like Harris Museum in Preston and Rochdale Art Gallery seemed more willing to take a chance showing young unknown artists. I detect a shift towards less risk-taking in favour of more eye-catching shows (which has also taken place in theatres). And of course, online options have revolutionised the interchange of artist with audience and the marketplace.

You have now lived in Italy for many years. How has that worked in relation to developing your career as an artist, both in the UK and internationally?

My experience in Italy has provided an excellent means of 'looking back' objectively at Britain and my own culture. This was particularly useful in my survey of London, which took place, on and off, from 2000 to 2016. Although I’m fascinated by cities as laboratories for studying human behaviour, being surrounded by nature provides the necessary time and peace of mind for me to develop ideas based on the urban experience.

There is a preponderance of beauty in Italian culture and built environment which, frankly, I find seductive. But in this culture, I continue to produce works which reflect a British artistic tradition that focuses on the underside of life (the scruffy back-alleys of post-war Liverpool 8 of my childhood are obviously still in my DNA!). Interestingly, my current project, inspired by the beauty of the fresco technique exemplified by the great Italian masters, finds its expression in works destined to be seen as 'relics' in a bombed out-church.

There is a new generation of Black artists emerging across the country, many of them interested in discovering who went before them and to learn from them. What advice would you give to such artists working in Liverpool?

My advice to young black artists in Liverpool would be the same as to any young artists. My reasons are: firstly, I would argue that artists in the West are confronted with a dichotomy established at the birth of modern art in the mid-nineteenth century: the romantic notion of the individual artist driven by the need to express him/herself and trying to find a space, a) in which to be seen and, b) in which to sell their work in the art market. In my experience, this struggle (shared by musicians, writers, actors, etc.) is governed primarily by the discrepancy between available outlets and the number of artists trying to make a living.

Secondly, to suggest that there may (or, indeed, should) be a route for artists of a different ethnic make-up that is distinct from others perpetuates the myth of racial stereotype, and this can lead to a ghettoisation of the artist involved - “black artists do things differently, therefore they belong in a 'Black Art' category”. Most artists simply want to be themselves, and the challenge is to present one's work as honestly as possible, regardless of any 'isms' constructed by Western art.

A young black artist has to confront whatever circumstances he/she has grown up in and learn to forge their identity according to how they conduct this battle. If this means the work they create is consciously or unconsciously determined by their being black it rightly deserves acknowledgement in those terms. The trap arises when the public sees the artist only in these terms, especially when the same artist produces work not informed solely, or even at all, by the premise of being black.

Liverpool is a special place. Many black people are – like me – of mixed race. I always enjoy coming back to work in the city and am proud to be Liverpudlian. I hope young artists there can tap into its cultural traditions which is their heritage, and transform them with their own voices.

See Tony's work at Bluecoat from Wed 9 Jun, 2021.