The Bluecoat was saddened to hear of the recent death of Trevor Hughes who had a long association with the arts centre. Trevor ran the popular record and comic fairs for over forty years, hiring our spaces – the large room upstairs and, from 2008, the Sandon and Garden rooms – for these regular events. They provided not just a marketplace for collectors and dealers but an opportunity for music or comic enthusiasts to come together. That these were such social gatherings was down to Trevor’s enterprising zeal, as he worked tirelessly to promote the events, attract stall-holders – including from beyond the region – and occasionally lay on special guest appearances by music-world figures.

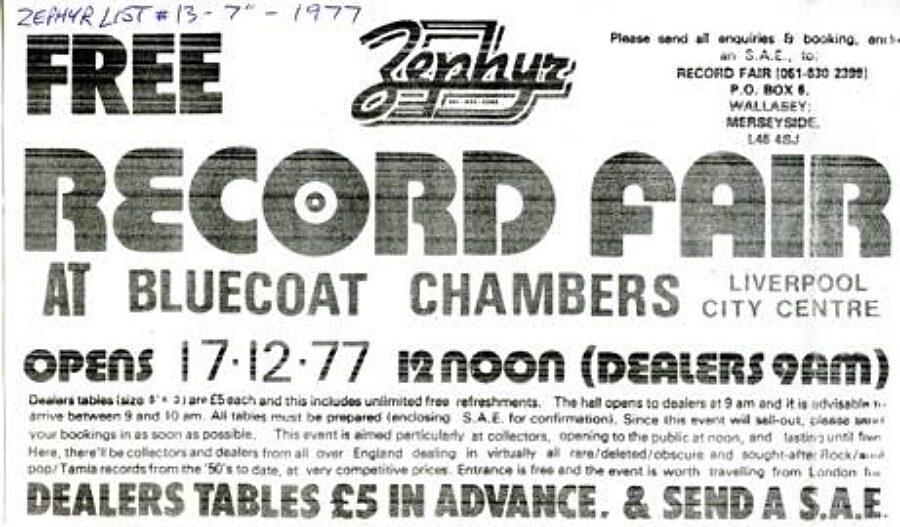

Trevor, who ran a record shop, Zephyr on Trafalgar Road in Wallasey on the Wirral, established the record fair at the Bluecoat in 1975, making it arguably one of the earliest in the UK and certainly one of the longest running. It continued, almost without a break (when the building was closed for its capital development, 2005-07) until the pandemic curtailed such events. In its heyday, the fair occupied the whole of what was then the Concert Hall, now the upstairs Bistro. Then, this was a flexible space used for a wide range of activities, from conferences to concerts, dance performances to craft fairs. Music has now largely disappeared from the Bluecoat, but for many years this space hosted live music – classical, folk, jazz, pop, reggae, ‘world’, experimental and much else, as surveyed in Roger Hill’s chapter, ‘Bechsteins and Beyond: Music at the Bluecoat, 1907-2017’ in the recently published book on our history, Bluecoat, Liverpool: The UK’s first arts centre.

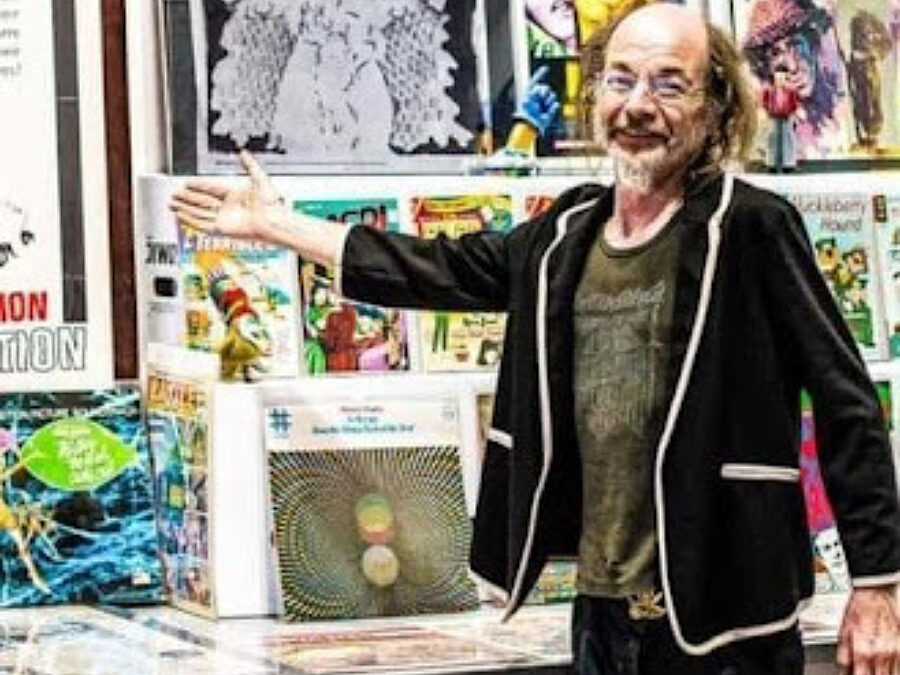

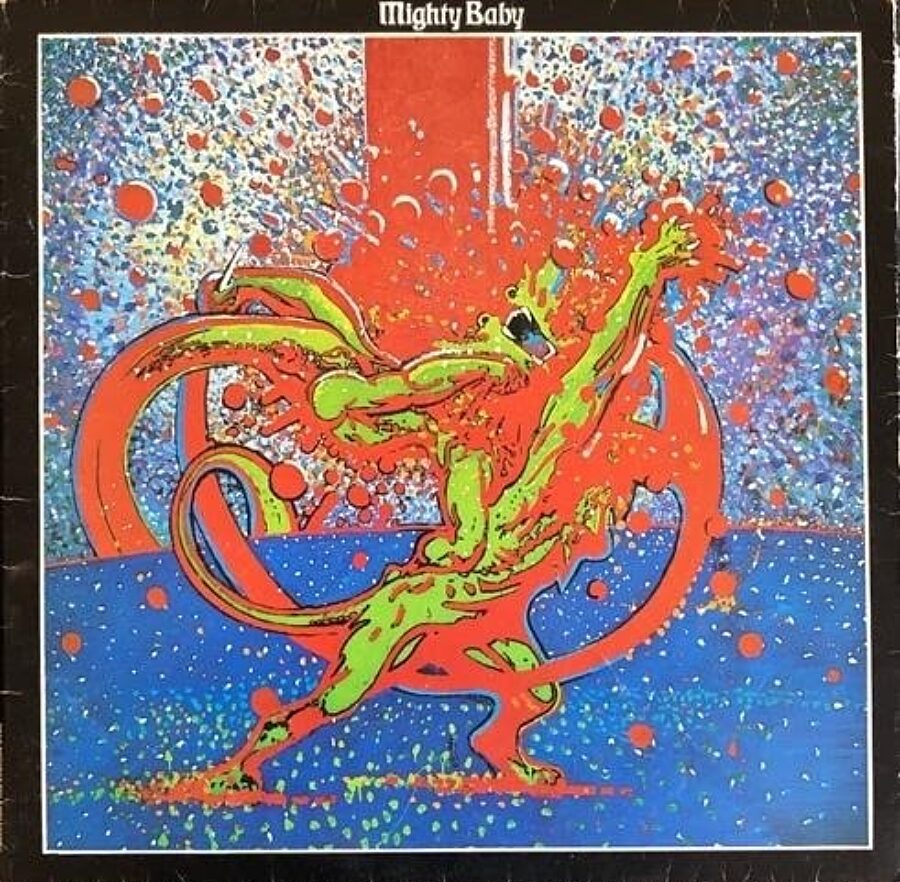

Trevor’s record fairs were an integral part of this eclectic musical mix. When I started running the gallery programme at the Bluecoat, I worked on Saturdays – our busiest day – and, being a vinyl junkie, I would often pop up to the fairs in the late afternoon as things were winding down. Of course, by that time all the bargains had gone, but I still managed to pick up some of my most treasured records, including the first LP by British psychedelic outfit Mighty Baby, the triple LP reggae collection The Trojan Story, and a rare Northern Soul 45, ‘Where is the love?’ by Glen Miller (no, not the big band leader).

Trevor’s own tastes were strictly psychedelic and prog rock, as attested to by Nigel Tudman’s vivid recollection of visiting his lair in Liscard in 1997:

‘The Dealer is holding forth on the subject of Van der Graaf (Generator), particularly a memorable gig in 1976, like it was last week. “(Peter) Hammill was standing on stage with an acoustic guitar, covered in sweat, wearing a kaftan. It was so special”…

‘Cutting a peculiar figure in an ancient brown sheepskin coat and a pair of pre-decimalisation black cotton bellbottoms and Doc Marten retreads, The Dealer leads us down an alley and up a greasy fire escape to his grotto. A narrow corridor is made narrower still by the boxes of books and comics, the cabinets of collectible trash. We emerge into an ante-chamber, close to the heart of the archive… The records cover one wall, metal shelving floor to ceiling, representing 27 years of collecting, archiving and dealing. “To afford to keep 90% of this I have to be prepared to sell 10%. Some albums I cannot live without, others can go. My tastes are consistent, music I liked 20 years ago I will still listen to today”’.

Peter Hammill was a particular favourite of Trevor’s but it was the ‘space rock’ legends Hawkwind that he was most associated with, interviewing band members, following them on tour with merchandise, and publishing the fanzine Hawkfriends (later Hawkfrendz), packed full of material related to the band and ex-members like Robert Calvert. And from these obsessive roots, according to Tudman, ‘the collecting has spiralled out. Hawkwind endorsed the Krautrock of Can, Neu, Amon Düül and Faust, so The Dealer bought into it. He prefers Amon Düül, the others are “too repetitive, computer music”. But even more favoured are Grobschnitt and Eloy, the dodgy prog end of kraut – “very atmospheric, the early Pink Floyd with bits of Jethro Tull”’. At the same time Trevor was extremely knowledgeable about much American music of the sixties, especially the rock bands from the West Coast – the soundtrack to the Summer of Love - and the folk and protest movement, where Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton were particular favourites.

Tudman wrote about his visit to Trevor’s vinyl heaven in relation to a live art commission series called Mixing It at the Bluecoat in 1997 that explored the interface between visual art and pop. Following on from a project the year before, Live from the Vinyl Junkyard - devised as a response to the supposed death of vinyl with the rise of the CD - this series continued the theme, and two of the selected artists, Cornford & Cross proposed turning the Bluecoat’s art gallery into a record fair for a day. Trevor was the obvious person to go to and he duly staged a record fair, this time downstairs in the gallery, to the delight of record collectors and confusion of regular gallery goers.

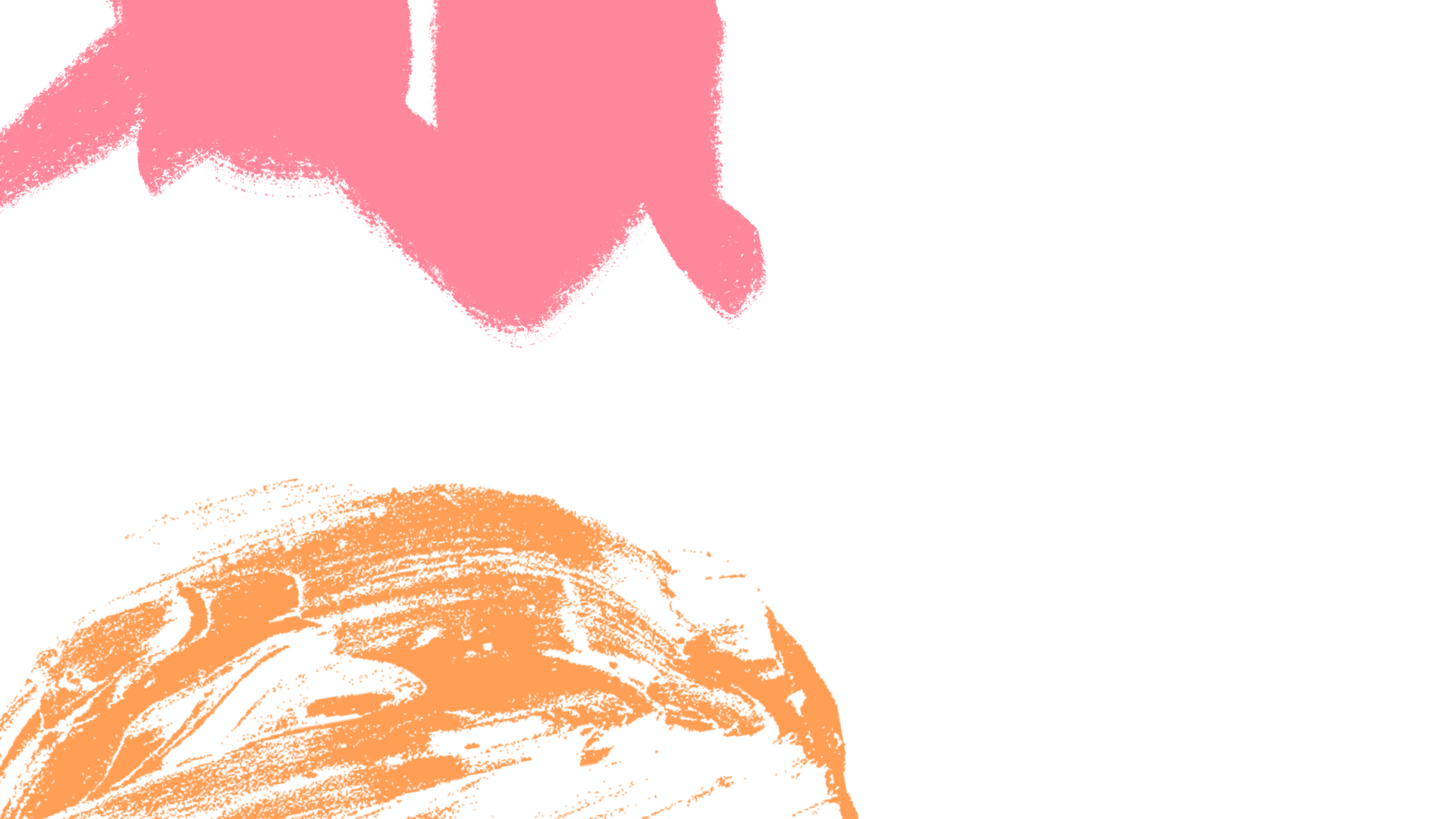

Trevor contributed to another gallery in the city, after I had introduced him to a curator at Tate Liverpool who was researching the exhibition, Summer of Love: Art of the Psychedelic Era (2005). Trevor had built up an extensive archive of psychedelic artefacts and counter-cultural ephemera from the 1960s, including posters, publications like International Times (IT) and Oz, films, books, and of course records, and he was able to loan much material to the Tate. I remember sitting with him, looking slightly bemused, at the swanky dinner after the private view for the exhibition. I seem to recall he was wearing his ‘Sunday best’, a facsimile blazer as worn by the actor Patrick McGoohan (aka ‘Number 6’) in the cult 1960s TV series, The Prisoner. Trevor is wearing it in the picture at the top of this post.

As well as being a font of psychedelic knowledge on Merseyside, Trevor also absorbed all manner of (particularly 1960s) popular culture and collected its artefacts with as much passion as his pursuit of insanely rare albums on the ‘swirl’ Vertigo label, the holy grail of psych and prog rock collectors, of which he had an almost complete set of originals. My one visit to his Wallasey lock-up revealed the breadth of his interests, with a vast array of toys, games, books, magazines, posters, sets of cards, as well as the records. There were original Fireball XL5 models and Daleks of all sizes, and I remember that at one record fair at the Bluecoat he had a life sized one of these cyborg aliens from Dr Who on guard at the entrance. At the fairs, hard-to-find items like radio and TV comedy records, film soundtracks or spoken word could be found, and even in the £1 section of middle of the road, easy listening and country & western, unusual obscurities would occasionally surface.

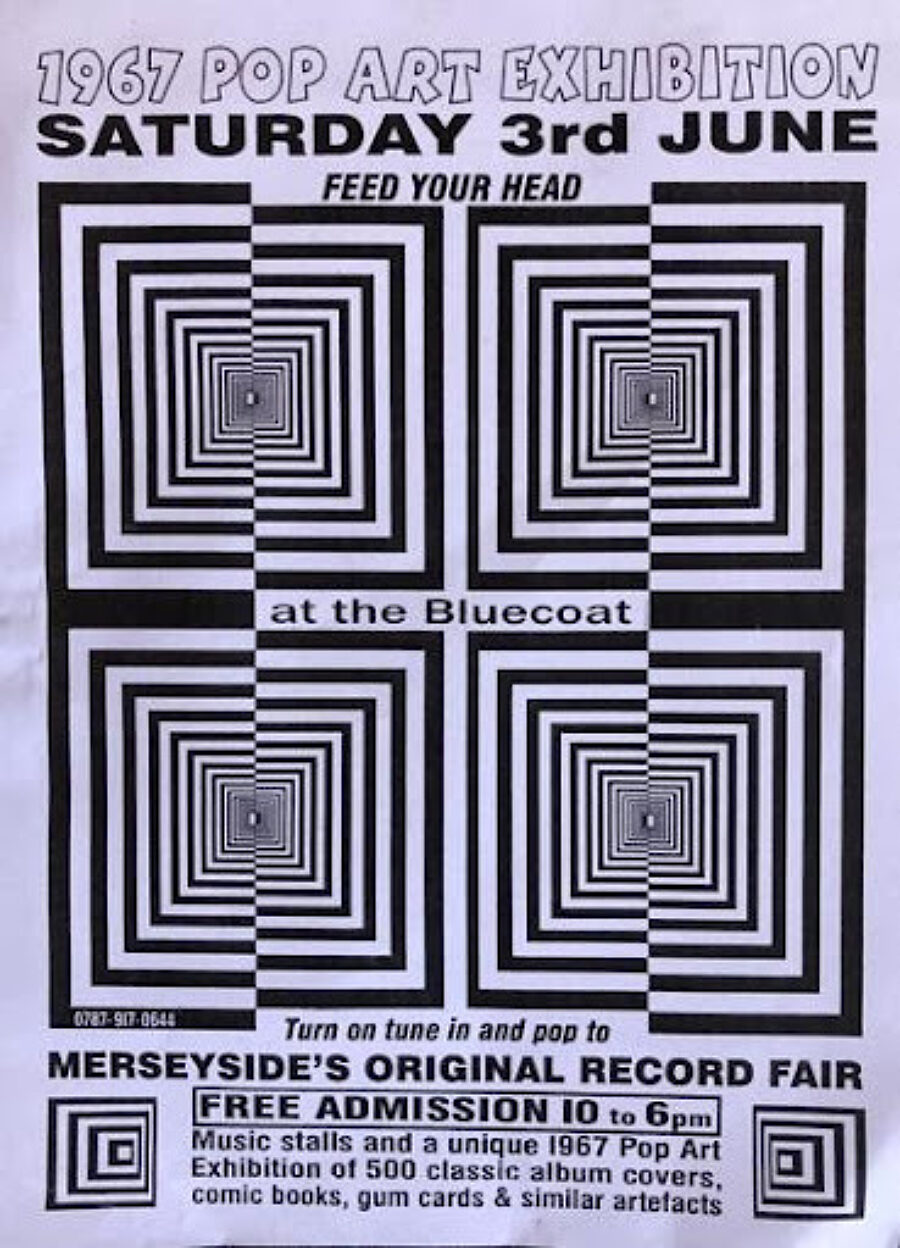

Trevor’s eclectic offer – from these bargain bins to the super-expensive collectibles displayed on the wall, out of reach behind the tables – invariably made a visit to his record fairs enriching. And he went to every effort to make them into special occasions on particular dates, usually during the August Bank Holidays when the international Beatles convention was in town. Then, he’d give the fair a Merseybeat flavour, with personal appearances from musicians from the era. Other invited guests included British psychedelic legends Arthur Brown (of The Crazy World, but without his flaming crown) and Twink, of The Pink Fairies and The Pretty Things. In 2017, in keeping with the 50th anniversary of Sgt Pepper being celebrated in the city, he organised alongside the record fair a 1967 Pop Art Exhibition in the Bluecoat’s Sandon Room, with 500 items from his collection.

In parallel with the record fairs, Trevor ran comic fairs at the Bluecoat, starting in 1974, but he struggled to revive these in later years, in contrast to the record fairs which flourished again thanks to the revived interest in vinyl. It was gratifying at the last few fairs to see the place packed with a mixture of young people and veterans of the collecting scene. If the fairs ever return, they won’t be quite the same without Trevor, but his presence will be there for all of us who enjoyed his company and for the pleasure he gave us in helping unearth that elusive, long sought-after seven or twelve inches of plastic.